Situated on the Warta River, Poznań is the capital of the region, Province and archdiocese, and an important point on the Piast Route.

St. Adalbert’s Hill is located somewhat aside but still not far from the very centre of the city. Apart from two temples (St. Adalbert’s church and St. Joseph’s Carmelite church), there is a Cemetery of the Merited, spanning over an area of 1.8 ha, overgrown with old growth of trees, and forming an extremely charming nook of the city. It is Poznań’s oldest functioning necropolis.

The cemetery was founded in 1808-1810, a result of the endeavours of Stanisław Kolanowski, a brewer, originally as a cemetery of St. Mary Magdalene’s Collegiate Church. As the parish received a new cemetery in Grunwaldzka St. in the late 19th century, in the area occupied today by the International Poznań Fair, the previous cemetery started being called the ‘old-parish cemetery’. An Immaculate Conception statue was erected there in August 1829. The first burial took place there on February 19, 1810; the earliest surviving gravestones are those of: Ignacy Sterzbecher (1810), Monika Zakrzewska, nee Sczaniecka (1813), and Rozalia Kolicka (1815). The nicest tombstone is the one of Aniela Dembińska, nee Liszkowska, a work of Władysław Marcinkowski (whose grave is not far from there).

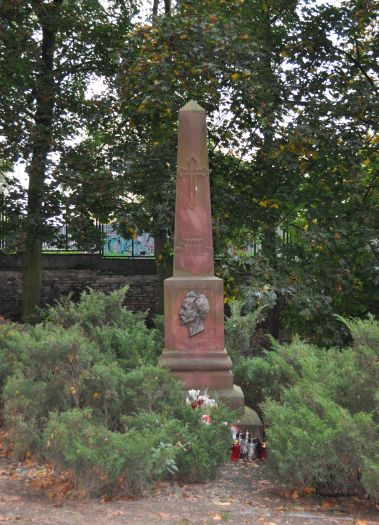

Walking through the cemetery, you can find graves of a pleiad of the most eminent figures of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century Poznań. Those include the city mayors (Presidents, in the Polish nomenclature), of whom the excelling personages were Jarogniew Drwęski, the first mayor appointed after independence was regained, and Cyryl Ratajski. Among the tombstones, an obelisk made of red sandstone (and reconstructed in 1985), devoted to Hipolit Cegielski, is pretty discernible. This gravestone is but symbolic as Cegielski was actually buried at the former St. Martin’s cemetery and his actual burial place has never been re-identified ever since, thus preventing any exhumation. The tomb of Raul Koczalski, the eminent composer and pianist, is easily recognisable by its lyre-like shape; further up, in the same row, is a tombstone of Jan-Konstanty Żupański, a well-known editor and bookseller. And then on, a more contemporary piece – the tombstone of General Stanisław Taczak, the first commander in the Wielkopolska Uprising.

The cemetery’s lowest-located part may seem empty and undeveloped. In the past, it was right there that victims to the cholera pandemics, which haunted the city repeatedly between 1831 and 1873, decimating its population, were buried in collective graves. Such burials were carried out in the night, tacitly and without a ceremonial setting, so as to avoid a panic in the town.

The cemetery had grown overpopulated by the end 19th century and only those deceased who had before then had their family graves there could still be buried in them; hence, with time, the cemetery got overgrown with increasingly exuberant vegetation, falling into oblivion. Individual identifiable graves of outstanding Wielkopolska dwellers were encompassed with care in 1930s. The outbreak of World War 2 caused that the action was discontinued – instead, a number of tombstones were damaged in February 1945, in the course of the fight for conquering the nearby Citadel.

In 1948, the cemetery was made the place of repose for merited individuals of Wielkopolska; then, in 1958, the Society of Lovers of the City of Poznań set up a Social Committee for the Cemetery of the Merited. These actions did not prevent progressing devastation and pillage of tombstones of historic interest, though. This remained so until 1981, the date the cemetery’s area was finally set in an order and provided with permanent guard.

Open daily fro 10 am to 6 pm.